The Pontic Greek bride (Hionides 1996:297).

By Sam Topalidis (updated 2025)

(Pontic Historian and Ethnologist)

[ Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ with a reference are my words. ]

Introduction

There is little written in English about Greek culture in Pontos (north-eastern region of Turkey adjacent to the Black Sea). This work attempts to address this gap in our knowledge by describing Greek Orthodox weddings in Hortokop (modern Hamsiköy), Kromni and Kars.

The Greek refugees from Pontos brought a rich cultural heritage, including their various wedding traditions, when in the early 1920s they were forced to leave their homeland for Greece.

In Pontos, matchmakers played an important role in arranging Greek Orthodox weddings and sadly sometimes the bride-to-be was not even consulted. The bride’s parents made the decision when approached by the groom’s parents or their matchmakers. In many instances, couples married at a very young age (S Papadopoulos 1983).

In Pontos, a newly married Greek girl was obliged to live in the house of her father-in-law and become a member of the household and perform chores. She had to maintain silence towards her in-laws until she was given permission to speak, which may be given after she had given birth to a child. Only when a family did not have a son, the husband of the daughter lived with his in-laws and took the surname of his wife (http://asiaminor.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=8993).

Byzantine Weddings

Aspects of Pontic Greek weddings had their roots in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire. The following is sourced from Talbot Rice (1967:159–161).

In the Byzantine empire, it was illegal for girls to marry under the age of 12 years old and boys under 14 years old. After parents had decided upon a union, the engagement was ratified by a written contract. On the wedding day, the visitors assembled dressed in white. The groom came, accompanied by musicians, to fetch the bride. She would be dressed elaborately in a brocaded gown and a finely embroidered blouse, her face covered by a veil. As her groom approached her, she would raise the veil for him to see her heavily made up face, supposedly for the first time. Surrounded by her parents, friends, torchbearers, singers and musicians, the bride and her groom would walk together to the church. In church, their respective godparents stood behind them, holding marriage crowns above their heads throughout the ceremony. Rings would be exchanged and from the 11th century, a marriage contract, which had been drawn up prior to the marriage, was produced for signature before witnesses. After the ceremony, all returned to the bride’s house to a banquet. (The association of crowns with marriage predates Christianity (Radle 2024).)

From the 7th century, it appears to have been the custom for the bridegroom to present the bride with a bridal ring and belt. A wife’s dowry was safeguarded for her. As in Roman Law, a husband had to leave his wife’s dowry to their children, but at the same time he had to bequeath her enough to live on should she survive him, by endowing her money, furniture and slaves.

Hortokop Weddings

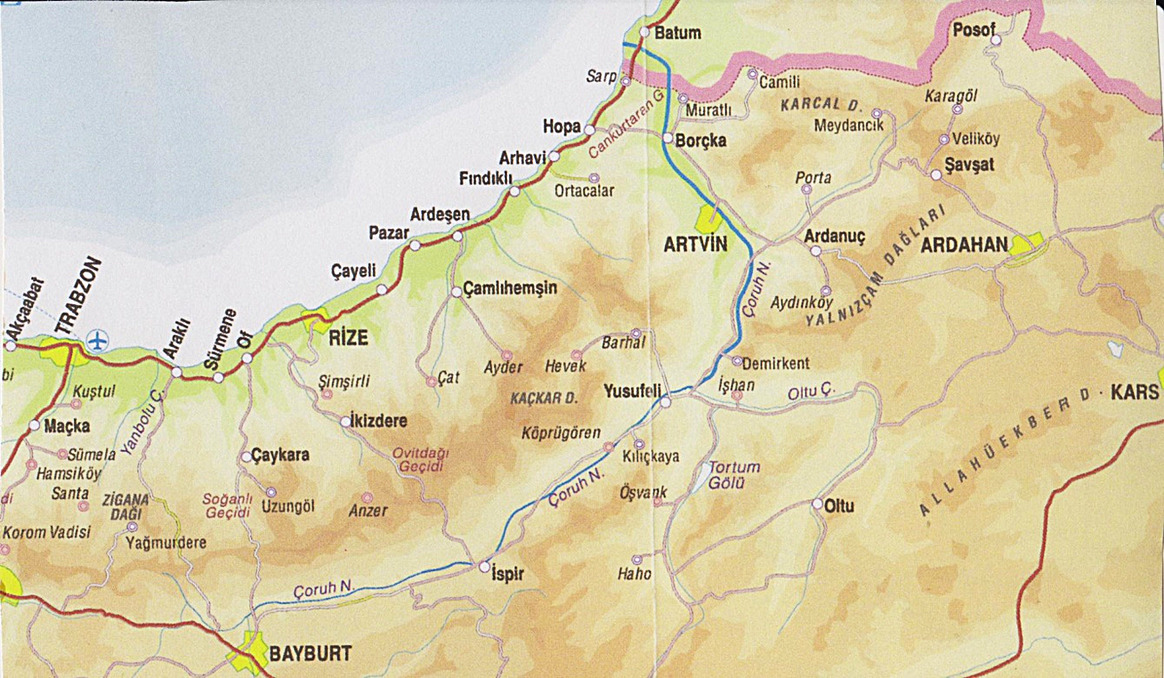

In 1857, it was reported that there were 80 houses in the non-nucleated Hortokop (modern Hamsiköy) village of which 60 houses were occupied by crypto-Christians, 20 houses by Greeks and none were Muslim. Hamsiköy is located 53 km south-west of Trabzon (Fig. 1) (Bryer 1983).

The following wedding preparation in Hortokop is sourced from A Papadopoulos (1954), in S Papadopoulos (1983). Preparations began immediately after the parents agreed to the wedding. [This particular wedding ceremony occurred at home even though churches were available.]

Wedding celebrations began on Thursday with the invitations and on Thursday evening, baking for the wedding also occurred. Bread called trigonia was baked for the groom and a special pie was baked for the bride.

Fig. 1: Map of Trabzon to Gümüşhane area (Euro-Holiday map, Turkey: Black Sea, East Coast; Trabzon to Gümüşhane = 64 km)

On Friday, the main meals for the wedding were prepared. The main course usually consisted of meat with potatoes (in winter).

On Saturday morning, the families of the bride and groom entertained their respective relatives. On Saturday night, celebrations began in both homes. The relatives and guests presented their gifts to the bride on Saturday night and to the groom on Sunday morning.

On Sunday morning, the bridal maids dressed the bride for her wedding at home. The bride’s wedding clothes included white woollen stockings, a blouse, kepsin (worn under the zipouna), koutnin spaler (silk and cotton-like material worn around the chest), the zipouna, a cotton or woollen dress with slits at the side of the legs, a blue apron [and a short open overcoat worn over the zipouna] and two kerchiefs, one worn on top of the other (Fig. 2; Plate 1). [It appears that the women did not wear the tapla, the small circular head ornament.]

On her forehead she wore perpentoulia, made up of beads and imitation gold currency hung from a red ribbon and tied to the back of the head. The bridal maids dressed similarly to the bride, except for the veil. When it was time for the groom to enter, the bridal maids placed a white veil over the bride’s face.

Fig. 2 The Pontic Greek bride (Hionides 1996:297)

Early Sunday morning, the best man would be collected from his house by the groom and his friends, with Pontic lyra music and a large lighted candle. Returning to the groom’s house with the best man and guests, dancing began with daouli (drum) and zourna (a double reed musical instrument of the oboe family) while the shaving of the groom occurred.

Parents, relatives and friends then offered gifts to the groom. A table of food was made available to those present. Then the retrieval of the bride occurred. The father of the groom was the first out of the house, followed by the groom, the priest and others. They rode to the bride’s home on horseback, taking a horse for the bride. When they reached the bride’s parent’s house, the groom and the best man would go to the house. The groom would take out a sharp double-edged knife and after making the sign of the cross, stick the knife into the top of the door. His future mother-in-law would come out and present him gifts. After they entered, the groom would then present his gifts to his bride.

Plate 1: Wedding zipouna dress from Trabzon (Benaki Museum Athens, 2017, author’s photograph)

The priest and some relatives would then enter and the wedding ceremony performed. [There was little detail provided on the ceremony.] When the priest shouted, ‘Isaiah horeve’, men would slap the groom. Wheat was thrown at the newly-weds and the priest would offer them wine.

After this, the wedding party returned to the groom’s parent’s house. The bride rode the horse which had been brought for her. Along the way, the best man would take the pie that was made for the bride and throw cut pieces to the following crowd.

When they arrived at the groom’s parent’s house, the bride would be helped off the horse. She would then enter the house with her right foot first. After she was greeted, dancing followed.

It was expected that the bride would not talk to her in-laws but communicate with them through signs or gestures. This silence was called Strimnoman.

Kromni Weddings

In 1857, it was reported that in the 10 villages in Kromni, over 35 km north-east of Gümüşhane (Fig. 1) there were 1,080 houses of which 67% were occupied by Greeks and 32% were occupied by crypto-Christians (Note 1) (Bryer 1983:37–38).

Andreadis (2007) described the courtship and wedding ceremony of Greek crypto-Christians, based on information from Papanikolas who had been a vicar in Kromni. Because of their status as crypto-Christians these ceremonies did not occur in churches.

Pontic Greek weddings in Kromni often occurred with girls aged between 12 and 14 years of age. The boys also married young, although most were older than their brides (Note 2).

The crypto-Christians avoided match-making their girls with male Muslim Turks as the girls would then become Muslims. However, they would accept a Muslim bride as she could be isolated until she became a Christian. Incredibly, in Kromni, a Greek bride did not visit her parents until after a year of marriage.

There were no Greek weddings during the four great fasts; the six weeks of Great Lent, the fast of the Holy Apostles which ended on 29 June, Domition, from 1 to 15 August and the Christmas fast from 14 November to 25 December. Local Kromni tradition also prevented weddings occurring during May or in leap years. Kromni crypto-Christian weddings proceeded with the following steps.

The proposal (psalapheman)

The parents looked for the right bride from the right family for their son. After the prospective bride was chosen, the boy’s parents entrusted women match-makers to propose to the girl’s family on their behalf. If the girl’s parents were in favour of the match, then negotiations for the girl’s dowry would proceed. The dowry was usually money, land or household gifts given to the groom’s family by the bride’s family. (According to http://asiaminor.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=8993 in Pontos, clothes were a considerable part of the dowry when the dowry did not include any real property.)

The engagement (soumademan)

The engagement followed after the girl’s parents accepted the proposal. The engagement ceremony occurred at night in the girl’s parent’s house where the young man, the parents of the couple, perhaps a few relatives and the priest were present. The priest took the rings and said three times, ‘in the name of God and with the blessing of the parents, we have come to engage (the groom’s name) with (the bride’s name), what do you say?’ The groom responded. The bride, who waited in another room, was then asked by the priest for her response. The priest then blessed her and rejoining the groom’s family gave them the bride. [The bride wore a veil.] The wrapped wedding rings were given to the priest and he completed the engagement service. During the period of the engagement, the groom rarely visited his bride and when he did, he was accompanied by his family.

The wedding

Weddings always took place on a Sunday with preparations taking many days. The groom underwent a ceremonial shaving. For the wedding, the bride would be dressed in her wedding finery, which included a pink zipouna (dress) and close-fitting jacket.

The placement of crowns (in the shape of a bishop’s mitre) on the heads of the bride and groom was performed by the priest together with the best man [expected to be in the bride’s parent’s house]. The crypto-Christian priest then offered milk with honey (not wine) in a cup to the couple and the best man. The priest then broke the cup underfoot. During the ‘dance of Isaiah’, the priest, followed by the best man, the groom, the bride and the bridesmaid (if there was one), all held hands as they circled the wedding table. While this was happening, the guests scattered korkota (a mixture of candy, raisins, nuts and small coins) over the newly-weds. At each corner of the table, they stopped and the newly-weds kissed the corresponding side of the Gospel, which was on the table.

When the ceremony ended, the priest wrapped the crowns and then he took off the bride’s veil. For some in the groom’s family this was the first time they saw the bride’s face. Amazingly, in some cases, it was the same for the groom!

Then followed the charisma (the giving) when the relatives of the groom gave presents to the bride. Then the musicians played in the wedding feast while the couple danced Omal. This was followed by the thymisma (the remembering), in which the dancers held lit candles bound together on a single wreath and accompanied by the musicians, danced in rhythmic steps to a song of benediction.

In Kromni, the bride maintained her silence to her in-laws, for one or two years and in some cases for life. Her silence only ended when her in-laws gave her permission to talk in their presence. This process of the new bride keeping silent was an effective way of reducing arguments in a household where many people lived.

Wedding from Kars

Kars is a town in north-eastern Turkey, over 400 km by road east of Trabzon, situated on a plateau 1,750 m above sea level near the border with Armenia (Fig. 3) (www.britannica.com/place/Kars). Kars’s population is 78,800 (2025 estimate) (https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/turkey/kars).

The following description is based on fieldwork by Zografou (1993) on Pontic Greek weddings conducted in a Pontic Greek village near Thessaloniki, in the north of Greece. The villagers were Pontic Greek refugees who had come from a village in the Kars region. [There is a gap in some of the information.]

Fig. 3 North-eastern corner of Turkey, east of Trabzon (Trabzon to Batum = 180 km, Nişanyan and Nişanyan 2001:218)

Before the ceremony

a) The best man’s invitation and the feast of the groom.

On Saturday evening, friends and relatives of the groom gather at the groom’s house where they tie a red ribbon around the neck and the legs of a rooster and accompanied by musicians, proceed to the best man’s house. The man who holds the rooster and a woman lead the procession, dancing with the rooster accompanied by music from the clarinet and the accordion. (In Kars, the musicians played the zourna or tulum (bagpipe) and daouli (drum).)

When they arrive at the best man’s house, they hand him the rooster after they receive payment. Then the best man and the invited people, together with the wedding procession dance back to the groom’s house, where a feast takes place until sunrise with music and dancing. The musical instruments included Pontic lyra, clarinet, drums and harmonium.

b) The bride’s feast and the gifts to the bride.

On the same Saturday night, a feast takes place at the bride’s parent’s house. After the feast at the bride’s and the groom’s houses had commenced, the bride’s future mother-in-law and relatives give presents to the bride. In Pontos they gave household goods. (In Greece, the feast takes place in a tavern.) When the mother-in-law arrives, she dances the Omal Kars led by the bride (www.youtube.com/watch?v=DB5mAU45_CU&list=RDDB5mAU45_CU&start_radio=1). Then the mother-in-law and her relatives return to the groom’s feast.

Before midnight, young boys and girls take the wedding-gown to the bride’s feast. Here they form a circle and the leader holds the wedding-gown dancing Omal Kars and Tik Diplon (www.youtube.com/watch?v=sd6K-OqTxdA&list=RDsd6K-OqTxdA&start_radio=1) until the money offered satisfies the group. Then the group returns to the groom’s feast. The groom was not allowed to see the bride.

c) The embellishment of the bride.

At noon on Sunday in the yard of the bride’s parent’s house, musicians play Pontic tunes. The bride’s relatives and guests dance in the yard, while the closest relatives prepare a roasted rooster and an omelette. Inside the house, the bride is dressed by her friends.

d) The shaving and the dressing of the groom.

On Sunday morning, the shaving and the dressing of the groom takes place at his home assisted by his relatives and friends while musicians play Pontic tunes. Once the groom is ready, a procession is formed, led by the musicians as they dance the Tas to the bride’s parent’s house.

e) The collection of the bride (nyfeparman).

The groom, his mother and the best man bring out the bride from her parent’s house. Prior to this, the best man pays a silver coin to the bride’s relatives who block the door. When the door opens, they offer the best man a piece of the roasted rooster and the groom the omelette. The bride stands in the middle of the room. The groom must now find the bride’s hidden shoe which is accomplished by paying for its return. Then the groom kisses the bride, while the mother-in-law ‘breaks’ the cake on the bride’s head [this must be an old tradition], handing out pieces of the cake to the bride’s friends. Then they all walk out of the house with the musicians playing the achpaston, the sad tune of separation. The bride and groom, the best man and the bride’s mother-in-law dance Omal Kars in front of the house. When all the relatives have danced with the bride, they proceed to the church.

The procession to the church and the marriage ceremony

A procession is formed, led by the relatives and the musicians of the groom followed by the bride’s group as they dance the Tas heading towards the church. Some of the participants have bottles of raki. In the church the wedding takes place. After the crowning, all greet the newlywed couple and then leave the church.

After the ceremony

After the ceremony, the procession dances the Tas to the groom’s house. The parents and close relatives of the bride do not take part.

a)The unveiling of the bride.

Arriving at the groom’s house, the bride’s mother-in-law welcomes the couple and lifts the bride’s veil to uncover her face (the apokamaroman). Then she offers a spoonful of red jam to the couple and to the best man. The mother-in-law, the newly-weds and the best man dance Omal Kars three times around in front of the door of the house. Then they enter the house where a table is covered with food.

In Greece, the feast begins with music and dancing at the village tavern for the wedding guests. The gifts to the groom are offered before midnight. Gifts are also offered to the best man.

b)The thymisman.

The thymisman is a slow ritual circle dance which takes place before midnight and is performed by seven married couples (who have been married only once) and the best man. The best man leads the circle with the groom’s parents, the newly-weds and all the others follow. The dancers turn around three times to the sound of the Pontic lyra. After the thymisman, the wedding is complete.

In Greece, many of the participants might continue feasting until the next day, while in the past, the Kotsagel dance took place in the streets in the morning after the wedding (www.youtube.com/watch?v=oUp46TmkQlQ&list=RDoUp46TmkQlQ&start_radio=1).

Conclusion

Information about Pontic Greek weddings have been collated to help our understanding of this ritual which is integral to our rich Pontic Greek culture and should not be forgotten.

The wedding culture of Christian Greeks from Pontos is being eroded as Pontic Greeks become more ‘homogenised’ in Greece or as they become assimilated in their new countries, such as Australia, Canada, Germany or USA.

Notes

Note 1:

Crypto-Christians in the Ottoman empire were people who had openly converted from Christianity to Islam but retained their Christian beliefs and practices in secret.

Note 2:

My maternal Pontic Greek grandmother was 15 years old when she married her 16 year old Pontic Greek husband in a village on the southern outskirts of Trabzon. My maternal grandmother’s Pontic Greek parents were only 14 years old when they married in the same area.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

Andreadis G (2007) ‘Faith unseen: the crypto-Christians of Pontus, part 1’, Road to Emmaus, viii(4):2–53.

Bryer A (1983) ‘The crypto-Christians of the Pontos and consul William Gifford Palgrave of Trebizond’, Theltio Kentrou Mikrasiatikon Spoudon [Bulletin Centre for Asia Minor Studies] Athens, 4:13–68, 363–365.

Hionides C (1996) The Greek Pontians of the Black Sea, Boston, USA.

Nişanyan S and Nişanyan M (2001) Black Sea: a traveller’s handbook for northern Turkey, 3rd edn, Infognomon, Athens.

Papadopoulos A (1954) ‘Gamilia ethima is to Hortokopi tis Matzoukas’ (in Greek), [Wedding customs in Hortokop of Matzouka], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 19:242–248.

Papadopoulos S (1983) Events and cultural characteristics regarding the Pontian-Greeks and their descendants, PhD thesis, New York University, New York.

Radle G (2024) ‘Byzantine dress in marriage rituals’, in Ball JL (2024) (ed) Byzantine dress: a guide,:145–162, Routledge, London.

Talbot Rice T (1967) Everyday life in Byzantium, Dorset Press, New York.

Zografou M (1993) ‘The role of dance in the progression of a Pontic wedding’, Dance Studies, 17:49–75, Centre for Dance Studies, New Jersey, USA.