Canberra, Australia

Traditional Greek Dance in Modern Greek Culture

Introduction

Traditional dance is an inextricable part of traditional Greek society and is at the very heart of social life, while, in urban industrial society it is given marginal significance.[ www.dance-pandect.gr/en/introduction-to-greek-dance/tradition-and-folklore-in-greek-dance/ ] When we learn the choreography of a traditional Greek dance, we are learning a dance that was performed only on certain occasions, performing the dance on other occasions could be seen as wrong. On such particular occasions, say, celebrating a saint’s day, dance would be only a small part of the event. Traditional dancers learned the dances by growing up with them as part of a local celebration. Young villagers observed dances years before they actually danced them, but they would have also taken part in the other activities surrounding the dance.[ folkdancefootnotes.org/begin/folk-dancers-type-1-of-3-traditional/ ]

From 1909, teaching traditional Greek dance in Greece was part of public school physical education and since 1983 it has been a subject of the Department of Physical Education and Sports in the public education system.[ Fountzoulas (2016). In addition, in the Greek speaking Republic of Cyprus, primary and secondary students have the opportunity to learn traditional Cypriot dances. ] In fact, traditional Greek dance is also taught at the Hellenic military academies and more specifically in the Hellenic Naval Academy.[ Kefi-Chatzichamperi and Chatzichamperis (2020). ]

Traditional costumes, music and traditional dance styles differ across Greece. At least 20 major regions and subcultures can be distinguished, each having at least 10 unique dances. Some dances are common to several neighbouring regions although the styles of dancing are different, as are the related songs and music. [There are literally thousands of traditional Greek dances.] There is no truly panhellenic dance, although some dances are widely performed. The most common dance form is the Syrtos. One particular Syrtos, the Kalamatianos, is considered a national dance (www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwexXwD13pI). The spectacular Tsamiko dance is also very popular (www.youtube.com/watch?v=gV7J9av0ihU).[ Raftis (1998:296). ]

Today, there are those who dance the traditional Greek dances they learned in their villages. There are others who learned traditional dances at a school of education and/or at a party. There are also those who belong to dance troupes who perform traditional dance out of its traditional social context.32

Traditional dance helps to bridge the gap between different generations, e.g. children can dance with their parents and grandparents thus providing a close bond. It also continues the culture of the national community and cultivates ideas of a distinct national identity. This could be seen as creating an ‘us’ and ‘them’ mindset.[ Kalogeropoulou (2013:61). ]

Public Feasts in Villages

In Greek villages, the dance is usually held in the church forecourt or the village square. The main dance often takes place in the late afternoon and continues until the following morning. Often the priest leads the first dance to bless it. Sometime in the past, a man did not hold a woman's hand during a dance, but instead held a handkerchief or scarf between himself and a woman in the dance line.[ www.dance-pandect.gr/en/dance-situations/patronal-and-public-feasts/ ]

The village community participates as onlookers of the particular dance being performed. Dance requires good music, song, food, drink and good parea (company). Creating the atmosphere of the moment creates the cultural event.[ Hunt (2004). ] The interplay between music and dance is crucial. If the music doesn’t inspire the dancers, the dance will have no Kefi. (Of course good weather is also needed.)

All dance occasions, e.g. saint feast days, weddings and the Sunday dances, were an opportunity for match-making and in many places these were occasions where boys could come into contact with girls. As the merry-making continued, the protocol was gradually relaxed and friends of both sexes danced together. What could be seen in traditional Greek dance was the order and position of people in the village dance circle. The circle can be divided into groups of friends or a family. The circle ‘speaks’ about the position people hold in the social hierarchy.[ www.dance-pandect.gr/en/introduction-to-greek-dance/ ]

Lead Dancer

In the past, men most often led the group dance when all people danced. [Women-only dances are obviously led by women.] There is less importance now for men to lead dances. However, there is perceived pressure on the lead dancer and this prevents some people from wanting to lead the dance.[ In addition, many will not join a dance if they are not proficient in the dance steps. ]

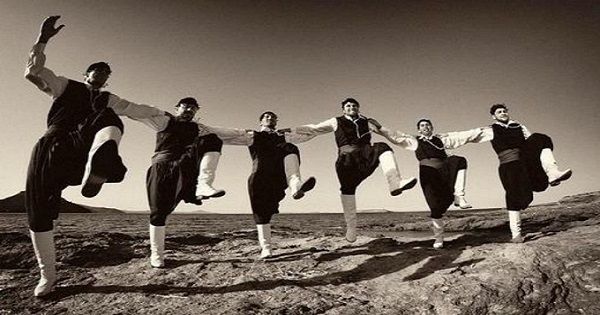

The handkerchief can be seen in traditional Greek dance held either in the right hand of the lead dancer (Plate 4.2) or being held between the lead and second dancer. [Nearly all traditional Greek dances move to the right.] Holding a handkerchief between the first two dancers allows more freedom of movement for the lead dancer and enables the second dancer to ‘hold and stabilise’ the lead dancer when he (or she) is performing certain improvised dance moves. In some Greek dances, e.g. the fast Cretan dance Pentozali[ The dance is also danced by women, but with more controlled steps. The Pentozali dance appears to have been created in the second half of the 18th century in Crete (Pavlopoulou 2011:54). ] (Plate 5.1), the arms of the dancers are stretched out holding their partners’ shoulders (www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MroY5S9CoM). If you can’t be moved by this YouTube clip, this document is not for you. The lead dancer in the Pentozali dance can also perform improvised leaps with corresponding slapping of his shoe(s) while being supported by the second dancer with him holding a handkerchief.

Plate 5.1: Pentozali dance (www.folk-way.com/en/pentozali-the-tradermark-folkdance-of-crete/).

The Tsamiko dance follows a slow tempo emphasising the grace of the dancer. The dancers stand shoulder to shoulder in the dance line with joined hands bent at the elbow at 90 degrees in the shape of a ‘W’. The second dancer needs a sturdy hand in order to support the lead dancer (holding a handkerchief) while the leader performs high acrobatic leaps, hitting his leg or shoe with his hand before landing. The steps have to be precise and strictly on beat. Improvisation is involved with many variations of the steps. In the past, it was danced exclusively by men, but today both men and women can take part in the dance.[ www.hellenicaworld.com/Greece/Dance/en/Tsamikos.html ] There is a women’s version of Tsamiko which is danced with smaller, more controlled movements.

Solo Dances

Zeibekiko

Some traditional Greek dances are improvised solo dances like the Zeibekiko (Plate 5.2) (www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QPO8HNTMuo) which became popular in mainland Greece after the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in the early 1920s. The Zeibekiko has no set steps and no particular rhythm. It requires an inner intensity by the dancers to express their feelings.[https://greekreporter.com/2021/12/03/history-tradition-greek-zeibekiko-dance/]

The Zeibekiko, while it was typically a masculine dance, it is now danced by everyone. It is sometimes referred to as the eagle dance because of its characteristic swooping turns and leaps of the body with the arms outstretched to the sides, knees slightly bent and head facing downwards.

Plate 5.2: Zeibekiko dance (www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QPO8HNTMuo).

The dance can often be characterised as a serious dance in comparison with most other Greek dances. The narratives of Zeibekiko song texts often reinforce a male chauvinism towards women. Of all the Greek dances, it is considered by Greek people as the most cathartic dance.[ Petrides (1980) in Tsounis (1995:95). ]

Tsifteteli

Another solo dance is the Tsifteteli, which is known as a belly-dance (Plate 5.3). It is characterised as a sensuous and erotic feminine dance, yet it is performed by everyone. The name is derived from the Turkish words cifte meaning ‘paired’ and telli meaning ‘stringed’ which refers to the stringed instrument which typically accompanies the dance.[ Tsounis (1995:93–94). ]

Tsifteteli does not have specific steps. When on the dance floor, performers can let themselves go and improvise. It is important that the hips sway, arms undulate and shoulders quiver. If performers are capable of swirling their belly [a difficult skill], then it gets even better. Contrary to other traditional Greek dances, emphasis is on the entire body. Tsifteteli has its origin in Anatolia [many disagree], but it came to the fore in Greece during the 20th century. The dance was adapted so that it could be danced by amateur women dancers as well as by men.[ Raftis (1995). ]

Plate 5.3: Greek women dancing the Tsifteteli dance (Source).

Performing Groups

General

A traditional Greek dance performing group is a collection of people who perform traditional Greek dances for an audience. [They obviously also dance for their own enjoyment.] Dancers strive to look the same: same costume for males, same costume for females, same smile and same movements. By way of contrast, the essence of traditional ‘village’ dancing in Greece is its spontaneity. People chat, argue, enter and leave a dance at will. All of these factors are missing in a stage performance. Almost all performing groups learn their dances from a teacher in a class setting. The teacher has probably learned the dances from another teacher and may never have seen a traditional dance in ‘the village’. Dances performed on a stage are removed from their context.[ folkdancefootnotes.org/begin/folk-dancers-type-2-of-3-performing/]

Today with the Internet, the choreography of traditional Greek dances performed around the world can be studied. It is important to encourage singing as part of our love of Greek dance! Singing in Greek while dancing is an important part of Greek culture and enhances our ability to speak demotic Greek and other Greek dialects like Pontic Greek.

Footwear

Footwear is important for dancers since different traditional Greek shoes enable the performance of certain kinds of steps.[ www.dance-pandect.gr/en/elements-of-traditional-dance/costume/]

When performing a dance on a stage (or a dance floor), ideally, the steps should be seen by the audience. For this reason, men, should not wear black shoes with black trousers on a stage with a black floor. Similarly, there is sometimes an issue with the length of women’s traditional Greek dresses that do not allow women’s dance steps to be seen. However, the flowing movement of the dresses stress the leg movements and turns.

In some Cretan dances, the men wear Cretan boots. Striking the floor with their boots while dancing and making a thud is important, e.g. in Pentozali (www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MroY5S9CoM).

Teachers of Traditional Greek Dance

General[ Raftis (1990).]

Teachers need to convey the following elements of traditional Greek dance to their students:

- Ethnological elements: name(s) of the dance, the locality where it is danced, (history of the place, its physical environment), related customs, the scene and atmosphere in which the dance is found.

- Functional elements: dance etiquette, behaviour, floor patterns, terminology and procedures.

- Costume: description of traditional dress and accessories; their production, maintenance and how they are worn.

- Music: the tunes and their interpretation, rhythmical patterns, songs and instruments associated with the dance.

- Kinetic elements: basic movements of the body, variations according to sex, age, circumstance, village and the possibilities of improvisation.

The teacher of traditional Greek dance must remember that dances are meant to be performed by groups of friends in celebrations. But the essence of these dances lies not only in their movements; it is inextricable from the context of their execution. They need to ensure that dancers thoroughly enjoy themselves.

Hand-holds

More emphasis should be placed on firm and guiding hand-holds in traditional Greek dance moving to the rhythm of the music which can help dancers move in unison.[ In a dance class, when dancing a simple dance like Kalamatianos, I believe, as an exercise, there is benefit in every second dancer in the dance line after the dance leader close their eyes while dancing. This allows dancers to appreciate the flow of their feet and hands to the music. ] The hand-holds should be firm enough to prevent adjacent dancers ‘from escaping’. (Like holding the hand of an older child when you cross a road.) The mere act of holding hands creates a bond of friendship and belonging. This is an important aspect of traditional Greek dancing.

Different hand-holds in traditional Greek dance include standing shoulder to shoulder in the dance line with joined hands bent at the elbow at 90 degrees in the shape of a ‘W’, crossed hands in front, holding onto your neighbour’s belts (from the front or from behind) as well as hands on shoulders.

Teaching adults

Traditional Greek dance groups are comprised predominantly of children, young adults and adults who have some Greek descent. More recently, ‘older’ adults, not only of Greek descent, have shown interest in joining adult Greek dance groups. When teaching traditional Greek dance to middle-age and older adults the following points are important:

- Before class, dancers need to stretch their legs, shoulders and back. They should also bring a bottle of water or a sports drink.

- Dancers should ideally perform simple drills before the commencement of dance class in order to get their timing right. For example, to prepare for Pontic dances, the foot movement is more flat-footed (rather than on the toes) and with a bouncing motion of the knees.

- Correct protocols for the class need to be explained, e.g. appropriate hand-holds between the sexes to prevent embarrassment. Some dances are designed for males or females only, but in the dance class these dances will be performed by both sexes.

- Wearing appropriate footwear to class is also important. Girls often wear flexible dance shoes with a heel (called a stage shoe) when dancing on a wooden floor. Some dance classes may be conducted on carpet and some people may get a better ‘feel’ by dancing without shoes. This is a personal choice.

- The first dance in class should be a gentle ‘warm-up’ dance, e.g. Kalamatianos. Similarly, the last dance should be to a gentle ‘warm-down’ dance.

- Dance classes need to be enjoyable. Laughing, talking and singing are important parts of the process.

- Older adults may not be able to leap and perform as energetically as they once did. Sadly, with maturity comes the accumulation of sporting and/or work-related injuries.

Dance classes also need to be enjoyable for the Greek dance teacher(s). After class, dancers should thank their teacher(s). Without dance teachers, there are no dance classes!

Conducting Traditional Greek Dance Workshops

During the mid-1970s, the first traditional Greek dance workshops were organised in Greece. However, they were mostly targeted at foreigners. These workshops evolved to become a large part of the traditional Greek dance phenomenon today. In particular, the participation of Greek dance teachers and members of dance groups has increased during the past 20 years. This is due to the interest in obtaining additional knowledge regarding teaching dance as well as learning a ‘new’ dance repertoire. At the same time, dance teachers-instructors wish to promote their dance knowledge by participating and teaching various dance workshops.[ Niora et al. (2019:95–96). ]

Most Hellenes now live in the large towns and cities of Greece. As a consequence, much of the performance of traditional dance has been cut off from its place of origin. Institutions that organise workshops for teaching traditional Greek dances need to be aware of the motives of their participants. They should better organise the activities that accompany the dance workshops and provide quality services for the participants. Activities need to include the explanation of traditional customs of the local community and visits to historical sites and attractions of the region. Finally, time needs to be scheduled to develop social relationships among participants.[ Efentaki and Filippou (2021). ]

Pontic Greek Dance

[ In Greece, the music most identifiable as Pontic originated from the area east of Ordu, on the Black Sea coast, especially in the areas around Trabzon, Gumushane and including Kars in the Caucasus. These dances differ from those of Greece and the rest of Turkey (Tsekouras 2016:140–141). ]

Pontic Greeks and other Christian Greeks still living in Ottoman lands were forcibly relocated to Greece in the early 1920s. (Many Pontic Greeks were still living in the former Soviet Union.)[ Topalidis (2019). ] Through the distinctive dances, costumes (Plate 6.1) and musical instruments (e.g. the three-string kemenche), Pontic dances connect Pontic Greeks to their social, geographical and historical origins. By the memories and emotions it evokes, Pontic dance [and song] becomes an expression of what it means to be Pontic Greek.[ Liddle (2016:63–64). ]

Plate 6.1: Kyriakos Moisidis in Pontic Greek costume (https://eefc.org/teacher/kyriakos-moisidis/).

Generally, Pontic dance movements are characterised by a vertical upper torso and an elasticity of the knees. Dance classes involve more than just performing the correct steps in unison. The unique shoulder shakes, arm swings and occasional forward bends, make Pontic dance distinctive from other Greek regional dances.[ Graziosi (1982:14). ] Steps are more flat-footed, rather than on the toes.

The most obvious visualisation of Ponticness is the dance Serra. It is a characteristic all-male dance.[ One version of Serra was recorded in 1960 performed by Pontic Greeks who were born in Pontos: www.youtube.com/watch?fv=OmuQOIbK0Fs Another version was performed at the closing ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ICDNe8re2NE I am always moved when I watch this footage. ] Many people incorrectly draw a parallel between the Serra as it is danced today and the ancient Pyrrhic dance. This is entirely false.[ www.dance-pandect.gr/pds_portal_en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=56&Itemid=58] Another spectacular Pontic Greek dance is Maheria (knife) between two men who dance with some improvisation while holding long metal knives (Plate 6.2).

Although the Serra and Maheria are spectacular Pontic dances, the most widespread Pontic dance is Tik which has many variations.[ Vavritsas et al. (2012). ]

There are two main periods of Pontic dancing identity in Greece—before and after the 1980s. After arriving in Greece and up to 1980, there was a tendency for Pontic Greeks to incorporate their music and dance within Greek public institutions. A single Pontic repertory was created to reinforce a common Pontic Greek sense of belonging. As a result, Pontic dances with Turkish connotations and dances shared with Armenians were excluded. The advent of a Greek socialist government in 1981 initiated an era of cultural awareness. As a result, a Pontic Greek dance identity started materialising. The inclusion of Pontic dance into the public school curriculum was a major advance. Dances with Turkish names were no longer excluded and new dances were introduced. Contact with dance troupes from Pontos in north-east Turkey enriched the dance repertory. [Recently such contact has been prevented by the Turkish Government.] As a result, dances and variations on existing dances or dances invented according to known motifs raised the number of Pontic dances to over 90. Through dance workshops in Greece, more ‘localised’ dances were disseminated.[ Zografou and Pipyrou (2011). ]

Plate 6.2: Pontic Maheria (knife) dance (www.youtube.com/watch?v=cYelSpTWVUw).

A Final Note

Traditional dance has always played an important role in the life of a Greek. It is an expression of life. The ancient Greeks danced at religious festivals and other community ceremonies; they danced to ensure fertility. Dance was regarded as one of the highest forms of art. Plato believed that every educated man should know how to dance. He advocated that girls should also be taught dance. He argued that such manly exercises kept the body strong and supple and ready for battle. The Pyrrhic dance (a form of mock combat) taken from Crete and perfected in Sparta, was the ideal.[ www.nostos.com/dance/]

Overall, traditional Greek dancing today is one manifestation of Greek identity and has important social and psychological benefits for those who take part. It creates a sense of overall well-being of a community. Additionally, the high social value of the activity within the Greek diaspora community is a manifestation of the importance of promoting Greek culture.[ Avgoulas and Fanany (2019:109). ]

In Greece, traditional Greek dance is considered to be so important that it is taught in Greek schools of education and the Hellenic military academies. It is also taught by cultural associations. Greek dance is still performed during religious festivals, baptisms, weddings and parties. In the Greek diaspora, traditional Greek dance is taught by the Greek cultural associations and God bless those teachers who share their Greek dance knowledge with their dancers.

References

Anoyanakis F (1991) Greek popular musical instruments, 2nd edn (Klint CNW trans), Melissa Publishing House, Athens.

Argiriadou E (2018) ‘Greek traditional dances and health effects for middle-aged and elderly people-a review approach’, World Journal of Research and Review, 6(6):16–21.

Avgoulas MI and Fanany R (2019) ‘The symbolic meaning of Greek dancing in diaspora’, Athens Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2):99–112.

Blagojević G (2012) ‘Research on dance in the Byzantine period: an anthropological perspective’, Pax Sonoris, VI:87–95.

Brubaker L (2021) ‘Dancing in the streets, Byzantine-style’, Argo: a Hellenic Review, 14:46–48.

De La Motraye, A (1727) Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa, (in French) Publisher unknown, Place of publication unknown.

Dimopoulos K (2021) ‘Are Sergiani dances female Byzantine dances? Common features in different periods’, International Journal of Education and Social Science Research, 4(3):369–401.

Dimopoulos K and Koutsouba M (2021) ‘Icons reveal: the place of the woman in dance in the Byzantine period through the churches’ and monasteries’ depictions’, International Journal of Education and Social Science Research, 4(2):254–270.

Du Mont J (1696) A new voyage to the Levant: containing an account of the moft remarkable curiofities in Germany, France, Italy, Malta and Turkey; with hiftorical obfervations relating to the prefent and ancient state of thofe countries, 2nd edn (trans into English), Publisher not stated, London.

Efentaki K and Filippou F (2021) ‘Motivation of cultural association members in Greek traditional seminars: differences due to demographic characteristics’, Journal of Tourism Research, 26:363–378.

Fountzoulas G (2016) ‘Academic research of Greek traditional dance in Greece and abroad: a critical review of dissertations and theses’, Congress on Research in Dance Conference Proceedings,:156–164.

Graziosi J (1982) Greek music tour, Winter 1982-Spring 1983, New York Ethnic Folk Arts Centre, New York:13–15.

Guys, PA (1783) Voyage litteraire de la Grece, Publisher unknown, Paris.

Hunt Y (2004) ‘Traditional dance in Greece’, The Anthropology of East Europe Review, 22(1):139–143.

Kalogeropoulou S (2013) ‘Greek dance and everyday nationalism in contemporary Greece’, Dance Research Aotearoa, 1:55–74.

Kefi-Chatzichamperi E and Chatzichamperis I (2020) ‘”EN XOPΩ”: the case of traditional dances in Hellenic Naval Academy’, Journal Sustainable Development, Culture, Traditions, 1a:27–36.

Liddle V (2016) ‘Pontic dance: feeling the absence of homeland’, Hemer SR and Dundon A (eds) (2016) Emotions, senses, spaces: ethnographic engagements and intersections, University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide:49–65.

Mandalaki S (n.d.) ‘Dance in prehistoric Greece’, XXIII Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, http://ancientgreekpandect.raftis.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Dance-in-Prehistoric-Greece-ENG-A.pdf

Niora N, Koutsouba MI, Lalioti V and Tyrovola V (2019) ‘The phenomenon of Greek traditional dance workshops in Greece: the case of the cultural association “En Choro”’, Journal of Education & Social Policy, 6(2):95–105.

Parcharidou-Anagnostou M (2004) ‘Dance in the post-Byzantine ecclesiastical painting (15th–19th century)’ (in Greek), Archaeology, 91:50–58.

Pavlopoulou A (2011) Musical tradition and change on the island of Crete, PhD thesis, Goldsmiths’ College, University of London, London.

Petrides T (1980) Greek Dances, 2nd edn, Lycabettus Press, Athens.

Raftis A (1985) ‘Dance in Greece’, Λαογραφία Newsletter of the International Greek Folklore Society, California, 2(8):2–7.

Raftis A (1990) ‘A call for a new breed of folk dance teachers’, Dance studies, 14:65–71.

Raftis A (1995) ‘A short essay on the Tsifteteli dance’ (Anastasopoulou A trans, 2007), En Choro (Dancing) 12, Dance and Eurythmics Association, Athens.

Raftis A (1998) ‘Greece: dance in modern Greece’, International Encyclopedia of Dance, Oxford University Press, New York, 3:296–301.

Topalidis S (2019) History and culture of Greeks from Pontos Black Sea, Afoi Kyriakidi Editions SA, Thessaloniki.

Topalidis S (in press) Greek Pontos, Afoi Kyriakidi Editions SA, Thessaloniki.

Tsekouras I (2016) Nostalgia, emotionality, and ethno-regionalism in Pontic Parakathi singing, PhD thesis, Graduate College, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois.

Tsounis D (1995) ‘Kefi and Meraki in Rebetika music of Adelaide: cultural constructions of passion and expression and their link with the homeland’, 1995 Yearbook for Traditional Music, 27:90–103.

Vavritsas N, Moisidis K and Vavritsas G (2012) ‘The Pontic dance ‘Tik’. Ethnographic and rhythmic element, Research in Dance Education, 15(1):83–94.

Wargo AC (2021) ‘The psychology of dance’, The Graduate Review, 6:35–40.

Xenophon The Persian expedition, Penguin Classics, (Warner R trans 1972), London.

Zografou M and Pipyrou S (2011) ‘Dance and difference: toward an individualization of the Pontian self’, Dance Chronicle, 34(3):422–446.